Being Adoptive Have More Fights in the Family?

Their parents are by and large well-educated and affluent. They receive more time and educational resources from those parents than the average child gets from theirs. Nonetheless they get into more conflicts with their classmates at school, display relative petty interest and enthusiasm about learning tasks, and register only middling academic functioning. Virtually whom are we talking? Adopted children. This is the paradox of adoption in America.

Reliable estimates on the school adjustment and academic functioning of adopted children have been hard to come by. State laws bar children from being identified every bit adopted in school records or vital statistics. Children living with two adoptive parents represent simply 1 percent of all children in the U.Due south., and so at that place are relatively few of them in national sample surveys of children and families. When special surveys on adopted children have been done, they have relied on parents as informants.1

To aggrandize what we know well-nigh adopted students, for this Found for Family Studies inquiry brief, I carried out a fresh analysis of information from a large longitudinal study of 19,000 kindergarten students that was conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics start in 1998. This study, known every bit the ECLS-K, contains plenty cases of adoption (160 children and families) for some reasonably robust estimates of its effects, at least in the early grades. Because the study began in kindergarten, we know the adopted children were all adopted early on in their lives, if not at birth. The ECLS-K has the farther advantage of being based on direct assessment of pupil knowledge and skills, and teachers' rather than parents' reports about classroom conduct.ii This is the first study of adopted children's school behavior that is based on independent instructor reports and makes use of a representative national sample of students from adoptive families.

Previous analyses of federal survey data indicate that adoptive families tend to be better off financially than other families with children in the U.s..3 This is partly due to cocky-selection and partly because of the screening that adoptive parents must go through before they are allowed to adopt. In addition, adoptive parents have higher levels of didactics and put more effort into caring for their children than biological parents exercise.iv Nevertheless my analysis shows that adoptees do not do too in school every bit one would expect from their highly advantaged home environments. The results phone call into question the widely held supposition that larger investments of money and fourth dimension in children can overcome the effects of early on stress and deprivation and genetic risk factors.

Classroom Conduct

Kindergarten and first-grade teachers were asked to rate the classroom beliefs of children in the ECLS-Grand sample—how well they got along with other children in a group situation. In both the fall of kindergarten and the jump of get-go grade, adopted children were more likely than biological ones to be reported to become aroused easily and often fence or fight with other students. In kindergarten, the boilerplate problem beliefs rating for the adopted group was at the 64th percentile, whereas for children with both nascency parents, information technology was at the 44th percentile. (Higher percentile ranks indicate more than problem behavior. The 50th percentile represents the boilerplate rating score for all students.) Children in single-parent, step, and foster families were at the 58th percentile as a group, not significantly different from the adopted group.

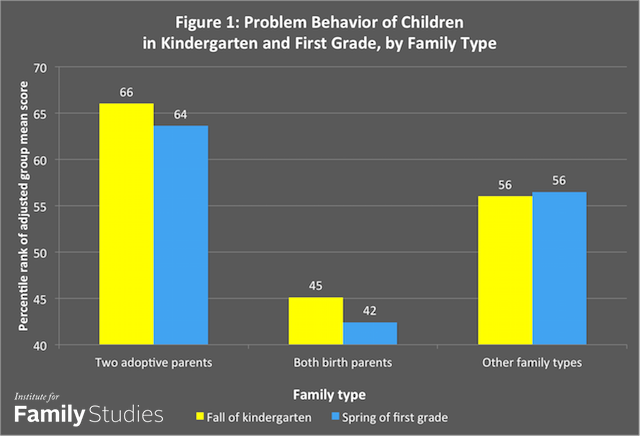

These gaps in problem beliefs scores in kindergarten widened slightly after adjusting for differences across groups in average kid age, parent education level, and racial-ethnic and gender composition, every bit shown in Figure 1. The adjusted average problem behavior rating for the adopted grouping was at the 66th percentile; for children with both birth parents, it was at the 45th percentile. After adjustment, adopted children showed significantly more problem behavior than children in single-parent, step, and foster families, who were at the 56th percentile as a group.

A like design was evident in the behavior ratings provided by first-grade teachers. Adopted students were at the 63rd percentile in raw instructor ratings of problem behavior, vs. the 43rd percentile for students from families with two biological parents. Students from other types of families were at the threescoreth percentile, not significantly worse than adopted students. Later aligning, the adopted grouping was at the 64th percentile, significantly worse than the both birth-parent grouping (42nd percentile), and not significantly dissimilar from students from single-parent, stride, and foster families (56th percentile).

Positive Approach to Learning Activities

Children in the ECLS-K were too rated by their teachers on how well they paid attending in course, whether they seemed eager to acquire new things, and whether they persisted at challenging learning tasks. Scores on these measures have proven to be predictive of later on academic operation and career success across elementary schoolhouse.v Adopted children were rated less highly with respect to such positive approaches to learning than were children being raised by both birth parents. In kindergarten, the adopted grouping's boilerplate rating score was at the 45thursday percentile, whereas for the two-biological-parent group, the average was at the 57th percentile. The learning-approach ratings for adopted students were not significantly dissimilar from those for students living with single or remarried birth parents or foster parents, who were at the 43rd percentile. (Higher percentile ranks indicate a more than positive approach to learning activities; the lthursday percentile again represents the average rating score for all students.)

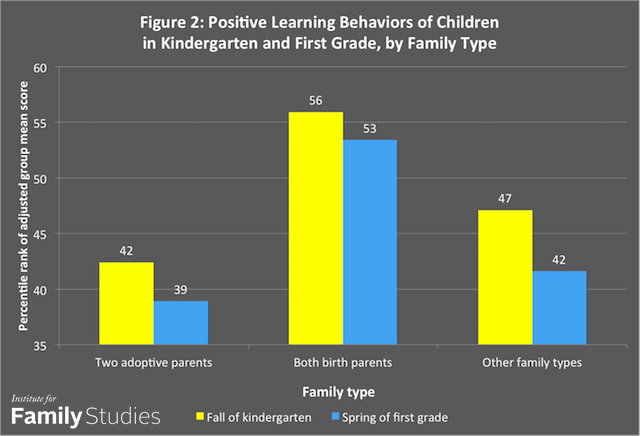

Afterwards adjustment for historic period, sexual activity, parent pedagogy, and racial-ethnic differences, the adopted group—now at the 42nd percentile—showed a significantly less positive approach to learning than children living with two biological parents, whose adjusted ratings were at the 56th percentile. The adopted group was as well lower than the single-, step-, and foster-parent group, at present at the 47thursday percentile, although this difference was only marginally significant.

The approach-to-learning ratings of first-grade teachers revealed a like pattern. Prior to adjustment, adopted children were at the 44thursday percentile, significantly lower than students with both nascence parents (56th percentile) and not significantly different from students from other family types (39th percentile). Later aligning, the adopted grouping was at the 39thursday percentile, significantly lower than the ii-nativity-parent grouping (53rd percentile) and not significantly different from the students from other family types (42nd percentile). The adjusted percentiles for both kindergarten and first-grade teachers' ratings are shown in Figure 2.

Early Reading Skills

In addition to gathering teachers' reports of children's behavior and attitudes, the ECLS-1000 tested children'due south academic skills. Hither, too, disparities sally betwixt students from different family types, though they are generally smaller in magnitude than on the measures reported above.

As the participating children began kindergarten, the ECLS-K assessed their pre-reading skills, such as recognizing letters by name, associating sounds with letters, identifying elementary words by sight. Adopted children seemed to perform these tasks fairly well: their average score on the reading assessment reached the 53rd percentile. This was not significantly different from the boilerplate score of children being raised past both nativity parents (55thursday percentile). And the adoptees outperformed children from other family types (unmarried-parent, footstep, or foster families), whose observed average score was at the 38th percentile.

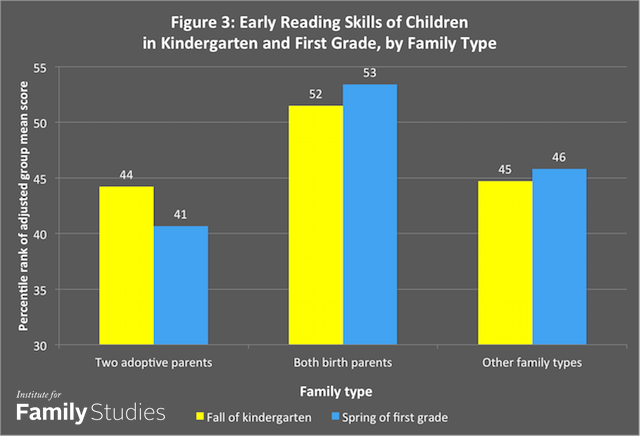

When the early reading scores were adjusted for differences beyond groups in age, sex, parent educational activity, and racial-ethnic limerick, a dissimilar picture emerged, notwithstanding. Equally shown in Figure three, the adjusted boilerplate score of the adopted group fell to the 44th percentile, primarily because of the loftier educational attainment of their adoptive parents. The adopted group was now not significantly different from the "other family unit types" group, whose adjusted score rose to the 45th percentile. The adjusted score for children with both birth parents besides went downwardly—to the 52nd percentile—but remained significantly college than that of "other family types" group.

The reading skills of well-nigh all students in the ECLS-K sample were assessed again in the jump of showtime course. Children were tested on grade-advisable skills like reading and understanding words in context. Once again, the reading skills of children with both birth parents (56th percentile) exceeded those of children in single-, step-, and foster-parent families, who were at the 41st percentile. Adopted children, at the 49th percentile, were not significantly more advanced than the latter group.

The flick was like later adjustment for demographic and socioeconomic differences across groups. Children with both nascency parents, at present at the 53rd percentile, were significantly more advanced than children in single-, step-, and foster-parent families, now at the 46th percentile. Adopted children, now at the 41st percentile, were not significantly behind the latter grouping (the apparent difference was non statistically significant due to a larger margin of error in this comparison).

Early on Mathematics Skills

In the fall of their kindergarten year, the ECLS-K assessed children'south pre-arithmetic skills similar counting by rote, recognizing written numerals, and agreement greater, bottom, and equal relationships. Again, the adopted children did fairly well. Their average raw score was near the same as that for all U.S. kindergartners, that is, at the lth percentile. Even so, they did less well than children with both birth parents, whose average math skills were at the 59thursday percentile. And their performance was non significantly better than that of children from single-parent, step, and foster families, who were at the 41st percentile (again, the credible difference was not statistically significant due to a larger margin of fault).

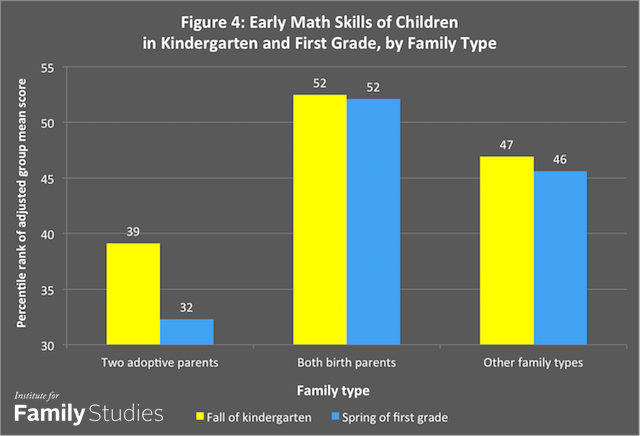

When children'south math scores were adapted for the same demographic and socioeconomic factors mentioned above, the performance of the adopted grouping was significantly worse than that of both the nascency-parent group and the "other family types" grouping. Equally shown in Figure 4, the adopted group's adjusted math score was at the 39th percentile, while the adjusted score of the both-birth-parent group reached the 52nd percentile and that of children from other family types was at the 47th percentile.

In first grade, ECLS-K children were tested on course-appropriate math skills like carrying out simple arithmetic operations. Students with both nascence parents were at the 56thursday percentile, significantly more than advanced than those from single-parent, pace, and foster families, who were at the 38th percentile. Adopted first graders, at the 40thursday percentile, were not significantly alee of that group. After adjustments for demographic and socioeconomic disparities, the percentile rank for adopted children fell to the 32nd percentile. Their adapted math performance was significantly inferior to that of biological children in ii-parent families (52nd percentile) and children in other family types (46th percentile).

Why Don't Adopted Children Do Improve?

The data presented in this research cursory show that adopted children in kindergarten and first class display to a higher place-average levels of problem behavior, exhibit below-boilerplate levels of positive learning attitudes, and score below boilerplate on reading and math assessments, despite their advantaged family background. Why don't the plentiful resources and strenuous nurturing efforts of adoptive parents lead to better classroom conduct and higher achievement by their adopted children? Possible reasons why family unit resource practice not always produce great outcomes may be found in zipper theory, traumatic stress theory, and behavior genetics.

Attachment theory holds that a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship with at least one adult, unremarkably the female parent, is essential for the mental health of infants and young children. Children who do not develop a stable and secure bond during early childhood, or have the bond disrupted, are subject to both short-term distress reactions and longer-term abnormalities in their feelings and behavior toward other people. Not having a stable maternal bond is apt to produce long-lasting deficits in the child's social development, deficiencies that are not easily remedied by a new domicile environment, no affair how favorable.

Some adopted children experienced fail, abuse, or other stressful events prior to their adoption. According to traumatic stress theory, the likelihood of long-term emotional scars depends on the intensity and duration of the stress. Severe or prolonged early stress tin take long-lasting effects on a kid's development, furnishings that a supportive adoptive family may but partly meliorate.

Behavior genetics is relevant because adoptive parents unremarkably cannot choose or command the genetic endowment of the children they adopt. Indeed, often they are non even fully informed about the educational attainments or occupations of the child'southward birth parents, nor do they learn much about their family histories. In other instances, adoptive parents consciously select children with known disabilities, hoping that the parental intendance they provide will enable the children to thrive.

Because the educational attainments of adoptive parents are exceptionally high, the genetic endowment of nearly children available for adoption is probable to be less favorable to intellectual accomplishment than the endowments of their adoptive parents. No affair how much intellectual stimulation and encouragement the parents provide the child, they may not be able to overcome the limitations of the kid's genetic heritage.

Probably all three of these theoretical perspectives have something to offer in bookkeeping for the paradox of adoption in America. Yet, none of the findings presented here is meant to minimize the tremendous contribution that adoptive parents brand to the children they have in or to lodge in full general. Many adopted children do reasonably well in school and enjoy lives that are far better than they would have experienced had they not been adopted. And they practice so at less price and burden to the public than if the children were raised in foster homes or institutions.

At the same time, it is of import for both prospective adoptive parents and policy-makers to exist realistic nearly what adoption can and cannot accomplish. The availability of the "adoption option" does not do away with the need for better prevention of unplanned and unwanted conceptions, then that fewer children are born into loftier-risk situations where they are likely to experience neglect or abuse and get in need of adoption.

Nicholas Zill is a psychologist and survey researcher who has written on indicators of family and child wellbeing for four decades. Prior to his retirement, he was the head of the Child and Family Study Area at Westat, a social science enquiry corporation in the Washington, D.C., area.

one. Bramlett, One thousand.D., Radel, L. F., & Blumberg, Southward. J. (2007). The health and well-being of adopted children.Pediatrics,119, S54–S60 (Supplement).

Zill, N. & Bramlett, M.D. (2014). Wellness and well-being of children adopted from foster intendance.Children and Youth Services Review,twoscore, 29–xl.

two. West, J., Denton, One thousand., & Germino-Hausken, E. (2000).America'south Kindergartners: Findings from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Form of 1998-99, Fall 1998. U.S. Section of Pedagogy: NCES Report 2000-070.

Zill, N. & W, J. (2000).Entering Kindergarten: A Portrait of American Children When They Begin School.U.S. Department of Pedagogy: NCES Report 2001-035.

3. Bachrach, C. A., London, Chiliad., & Maza, P. L. (1991). On the path to adoption: Adoption seeking in the The states, 1988.Journal of Wedlock and the Family53:705–18. Fisher, A.P. (2003). Still 'not quite as good as having your ain'? Toward a folklore of adoption.Annual Review of Sociology 29: 335–61.

Vandivere, S., Malm, Thousand., & Radel, L. (2009).Adoption USA: A Chartbook Based on the 2007 National Survey of Adoptive Parents. Washington, D.C.: The U.S. Department of Health and Homo Services, Part of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

4. Hamilton, L., Cheng, South., & Powell, B. (2007). Adoptive parents, adaptive parents: Evaluating the importance of biological ties for parental interest.American Sociological Review 72: 95–116.

Instance, A. & Paxson, C. (2001). Mothers and others: Who invests in children's health?Journal of Health Economic science xx: 301–328.

five. Duncan, 1000., et al. (2007). School readiness and afterward achievement.Developmental Psychology 43: 1428–1446.

Source: https://ifstudies.org/blog/the-paradox-of-adoption/

0 Response to "Being Adoptive Have More Fights in the Family?"

Post a Comment